June 25, 2022 / Spotlight on Art

The Still Life Practice of

Dana Zaltzman

I love to paint the story behind the object, most of the time I don’t know exactly what it is, but I know it's there – I create it.

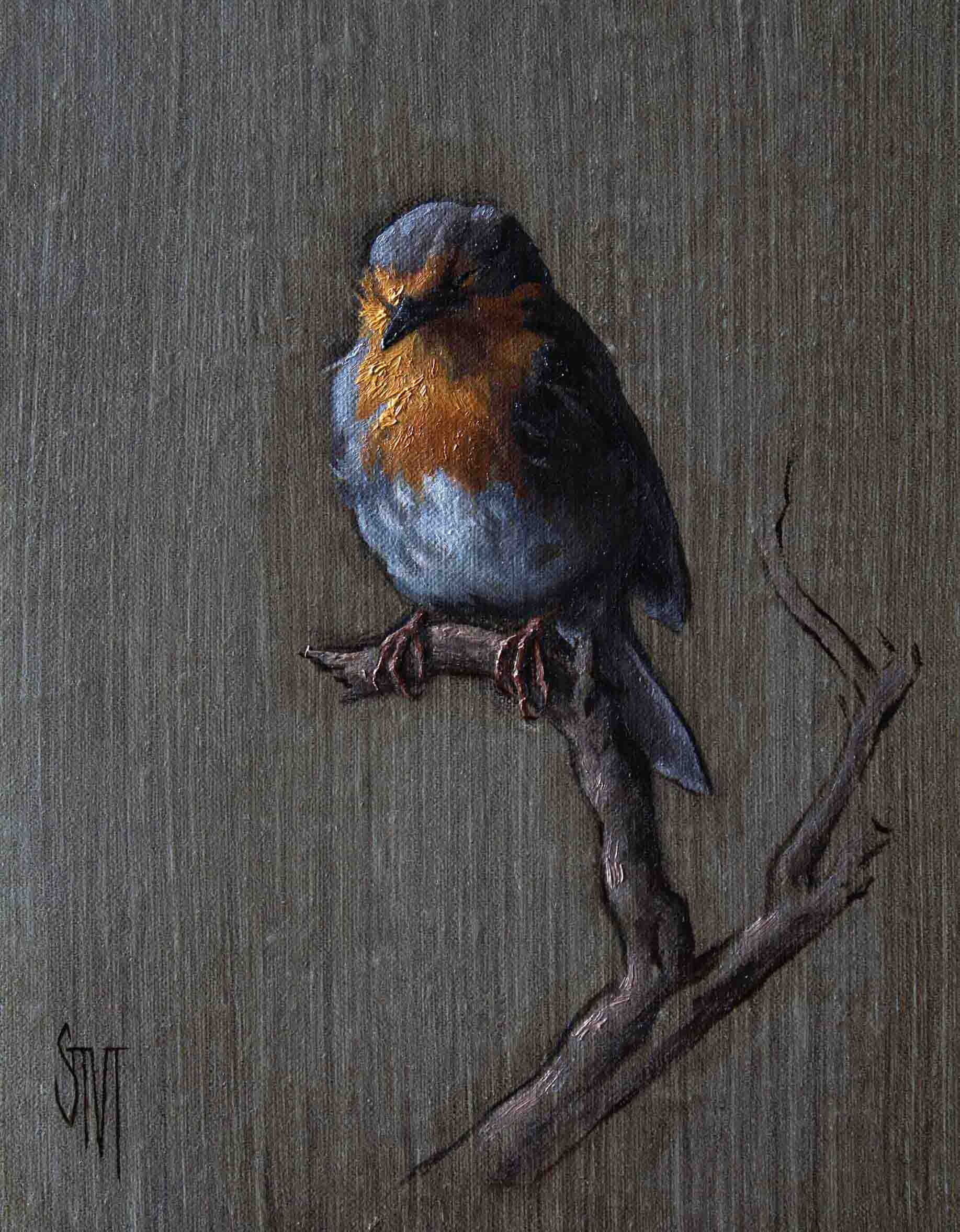

Dana Zaltzman, "Scale and Feathers", Oil on panel, 60 x 50 cm, 2017

The Florence Academy of Art graduate Dana Zaltzman has made a career of creating still lifes that while at first glance seem incredibly simple, have worlds beneath their surfaces.

Below is a feature on Zaltzman written by Dr. David Graves, touching on the specific qualities of the artist’s oeuvre of still life paintings while placing them in a context that decodes their cryptic symbology.

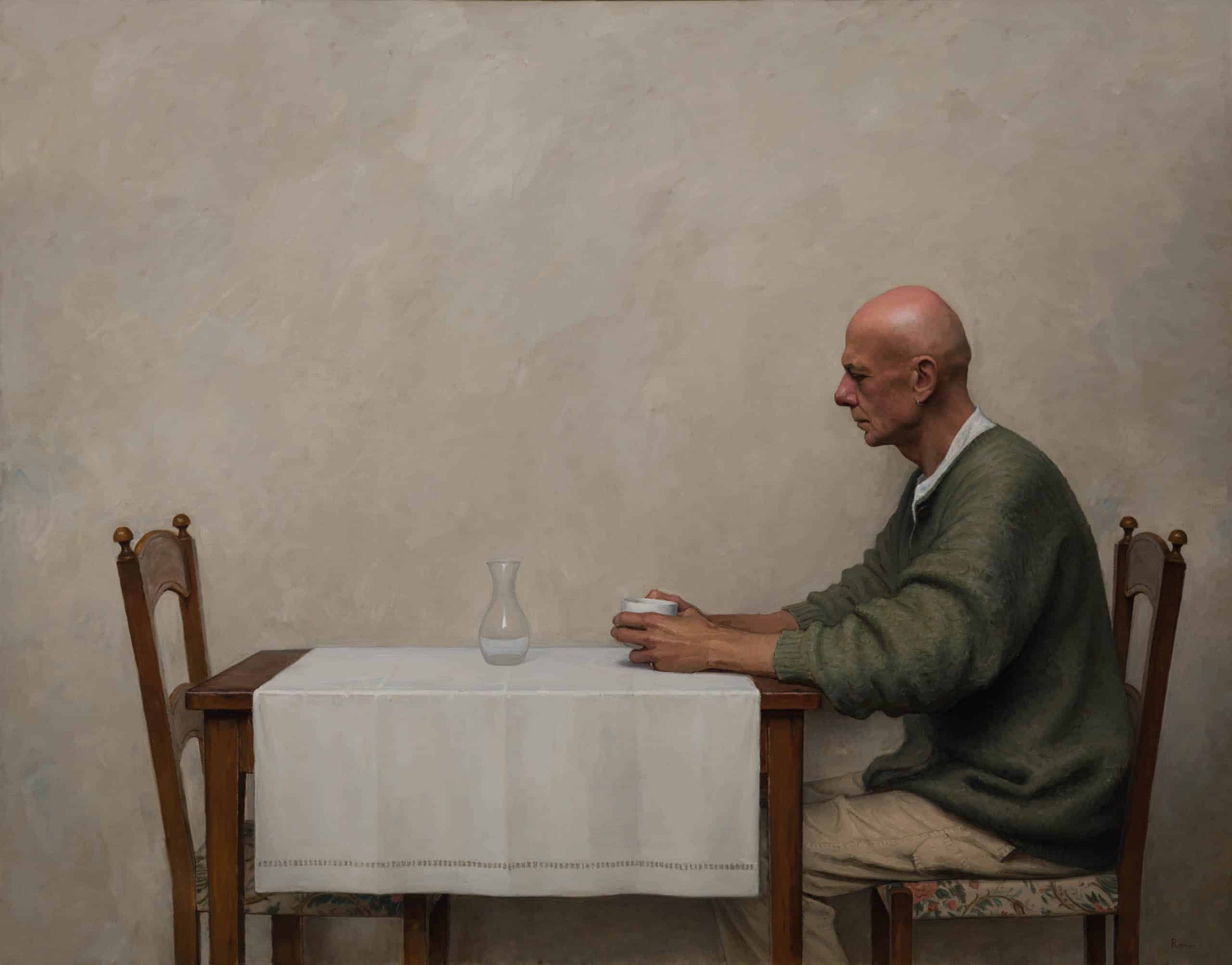

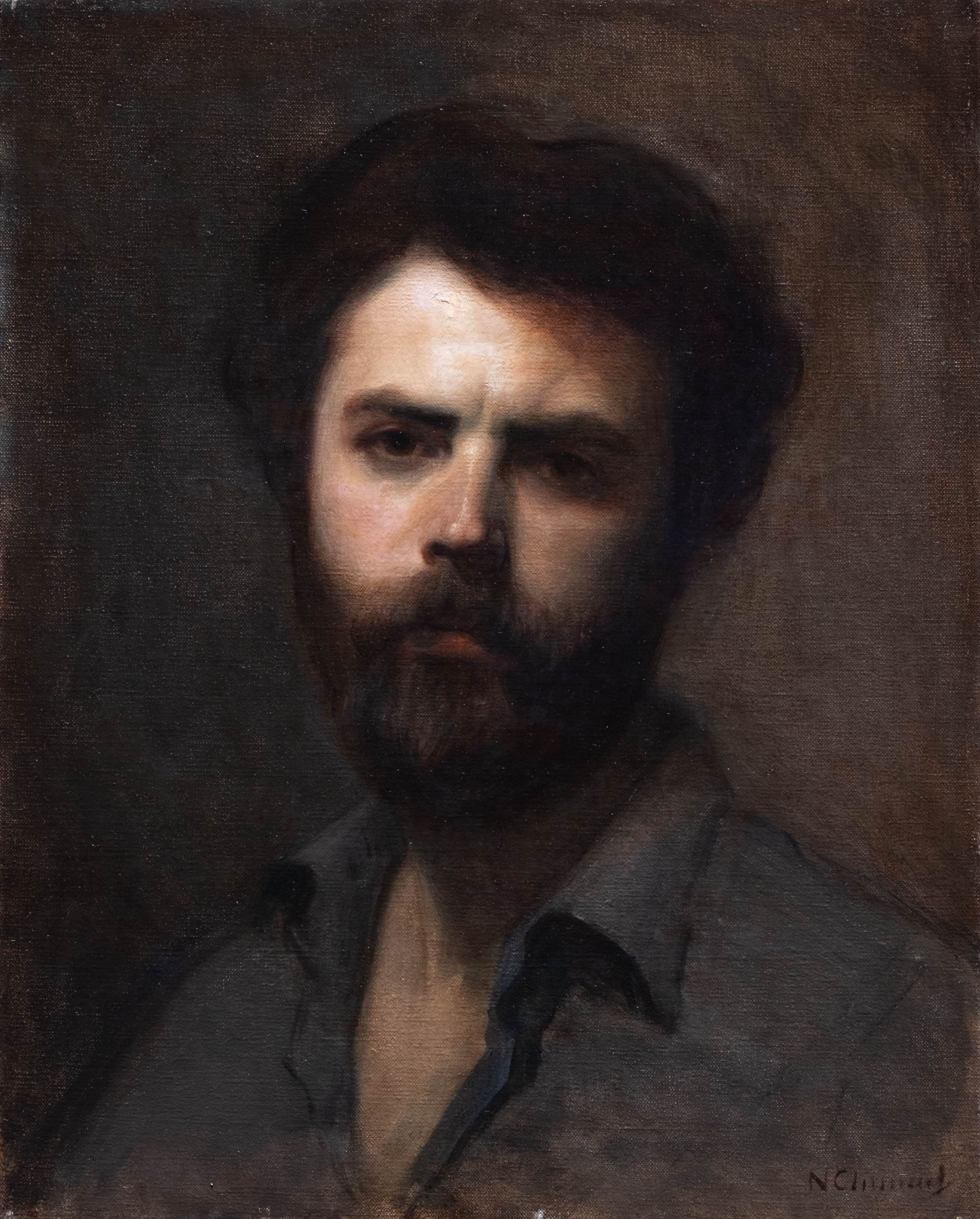

Dana Zaltzman

“Bricks and Pillow”

Oil on wood

50 x 80 cm

2019

“As a general rule, artworks reflect the culture in which they were created. One of the most fascinating things in examining a painting is to try and recognize this reflection of values, to discern how a specific painting expresses a certain way of life. Like solving a puzzle or decoding a cypher. And indeed, Dana Zaltzman’s paintings hold an enigma.

“Weighing feathers?” one might ask quizzically. “Coarse bricks on a pure white pillow?” At first it may seem that by painting still lifes, Zaltzman continues a rich tradition of Western painting. Today, many painters are exhibiting a renewed interest in still life. However, in contrast to 17th century Dutch still life masters, who tended to paint precious and exotic objects, many current artists turn to quotidian and not particularly impressive subject matters – a loaf of bread, a pickle jar, a tin of sardines… These painters of everyday life, perhaps inspired by artists such as Antonio López García or Israel Hershberg, focus on the “here and now,” shifting away from “deeper” meaning held in their painterly language. That is not the case with Zaltzman’s work.

Dana Zaltzman

“White cloth”

Oil on linen

90 x 80 cm

2020

Dana Zaltzman

“White cloth”

Oil on linen

90 x 80 cm

2020

For Zaltzman, the simplest of objects – a scale, a mailbox, a bird’s nest, a brick – are a portal to a rich and elaborate realm of ideas, possibilities, and sentiments. It seems that Zaltzman is fascinated by the straightforward truth of mundane objects. Each object has a story, a life story, if you will, and Zaltzman wishes to present it. However, the trick here (if I may) is that the object may be simple, but the story is not. In fact, the story is so not-simple that you cannot simply recount it, you have to show it. And so, Zaltzman places the object and its story under the spotlight of traditional chiaroscuro. The traditional treatment of light and shadow is not only a “dialogue” with baroque paintings, but rather plays a significant role in Zaltzman’s painting. The light uncovers, the darkness veils, and one does not exist without the other. There are things in the life story of a brick or a mailbox that are visible to the eye, and there are things that elude it. Light and darkness, visible and hidden, answers and questions, all of these are entangled with one another.

And perhaps it is a type of a yin and yang relationship?

Dana Zaltzman, “Silver pot and feathers”, Oil on wood, 30 x 40 cm, 2021

And indeed, one of the keys for deciphering Zaltzman’s painting code originates in a culture entirely different to the Israeli or Western culture – namely, Japanese culture and a few fundamental principles of Japanese aesthetics. One of these is Wabi, which refers to the beauty of the flawed, to imperfect beauty. In Japanese aesthetics, a beautiful object will look unfinished, imperfect, incomplete even. It shows its flaws, shows that it is still forming, and has yet reached its final stage of being. This perception is at odds with the perception of classical beauty of the West. In the West, the ideal beauty is perfect, eternal. In the West, the classical artwork strives for the absolute, the unchanging, the timeless. In the East, the opposite is true: Japanese classics strive to present a world that is constant dynamic formation, ceaselessly forming and dissolving. The concept of Wabi is rooted in ancient Chinese Buddhism, specifically in the notion of a world where everything is transient, fleeting, nothing is permanent, perfect, or even finished. When all things in nature, and all the objects we produce, exist simultaneously in the flowing river of reality, the fate of an object – its demise – is already known and embodied in it from its very inception. The Japanese call this “the pathos of things” (mono no aware). This notion indicates an extraordinary sentiment of empathy towards the ephemeral, from the rock-solid to the ethereal, from the metal weight to the duvet feather.

Still lifes of tin cans by Dana Zaltzman

In Tin Can, we are facing a scratched and beaten golden can, its lid is half closed (half open). What is in this can? It must be important, since it looks well used. Even the label has peeled off. But, as important as the contents of the can is, it must have run out. The open lid already seems permanently open, indicating that this can is past its heyday. Nevertheless, the can is still gleaming. Through the dents and scratches, the can radiates a golden light, illuminating its gloomy surroundings.

The other key concept in deciphering Zaltzman’s paintings is Sabi – beauty manifested in the surface of things that show their age. The golden can certainly displays Sabi, clearly displaying the marks of its age. The signs of age are in fact the history of the object’s life inscribed on its surface, like medals and decorations awarded by the military of life. The quality of Sabi is evident in the painting of a mailbox, a box that has seen better days, the rust and peeling paint recount its story. It is not just that this simple box was once shiny and new, it was also significant: It proudly represented apartment 10, displaying the family name at its bottom (already faded by now, “Keiser”?), it received the important mail messages. However, mail itself has also become obsolete and now old, unclaimed letters are carelessly shoved into the slot of the old mailbox. (It should be noted that in Zaltzman’s mailbox, as well as in Japanese aesthetics in general, Sabi and Wasabi often go hand in hand, creating an encompassing notion of Wabi-Sabi).

Dana Zaltzman

“Mailbox”

Oil on wood

60 x 50 cm

2018

Thus, in the painting Weight and feather for instance, the two sets of cultural ciphers, the European and the Japanese, function well. From the West, the painting is a contemporary still life of a prosaic object – a weight – focused in the center of the canvas. As though taking center stage, it is a heavyweight actor illuminated by dramatic chiaroscuro. Even though it is cast in cold iron, it displays a patina of fiery rust. In certain places, its metallic surface is evocative of the surface of the Sun, yellow-orange stains glimpsing through the iron oxide. So heavy that it leaves its round imprint on the surface beneath it. Despite its weight, it wears a single white feather, like a coquettish fascinator. The light feather is illuminated by an aura of extremely light, extremely cool blue-grays. With that Zaltzman creates a union of opposites – light and dark, heavy and light, hard and soft, warm and cold… Such opposites and their relationship served as the conceptual core of the 19th century Romantic movement in the West. Light and darkness, reason and emotion, nature and culture, life and death, all these were popular themes in Romanticism. From this perspective, one can recognize the Romantic nature ingrained in Zaltzman’s paintings.

Dana Zaltzman

“Weight and feather”

Oil on wood

31 x 30 cm

2019

Dana Zaltzman

“Weight and feather”

Oil on wood

31 x 30 cm

2019

However, the fundamental concept of the union of opposites, as the way things act in the world, is not exclusive to the Romantic West. The concept of yin and yang, which is also rooted in ancient Chinese Buddhism, serves as a logical-philosophical principle from which emerged an entire metaphysics in the Far East. The paradoxical pairings of light and heavy, rigid and soft, hidden and seen, which Zaltzman’s often calls upon, gain more profound meanings thanks to this cultural affinity with Far Eastern mysticism. And so, from the Western side, the opposites face one another in an eternal battle that is the origin of Romanticism. From the Eastern side, contrasts are also intertwined. Along with the stark contrast (bricks on a feather pillow), there can be no heaviness without lightness, no hardness without softness, no youth without old age, no light without darkness…

A series of still life paintings with bricks by Dana Zaltzman

No reality without fiction?

It would seem that the paradoxical pairings in Zaltzman’s paintings are less perplexing now. After all, she is in fact dialoging with two opposing world views – West and East. And so, she paints Western objects in a European genre, but the aesthetics of these images is Japanese. Therefore, Zaltzman’s objects look simultaneously realistic and fictional. Because this is the nature of life in the world of Zaltzman’s paintings. Sometimes the strong falls down, sometimes the delicate overpowers. At times the toughest of all needs some tenderness, other times the lightest of all needs to put down its full weight. And if these paradoxes urge us to stop and contemplate for a while in front of the painting, all the better.”

– David Graves

More about Dana Zaltzman

Dana Zaltzman was born in 1982, in Israel.

Dana began her artistic training in a college in the Northern part of Israel in 2005. At the same time she also took evening classes at the Academy of Figurative Art. After graduating in 2007, she traveled to Norway and studied with the Norwegian painter, Odd Nerdrum.

In 2009 she moved to Florence, Italy, and began the three-year drawing and painting program at The Florence Academy of Art, receiving her diploma in 2012

Dana lives and paints in Israel. Her work can be found in private collections around the world.

“I love to paint the story behind the object, most of the time I don’t know exactly what it is, but I know it’s there – I create it.

I work in my studio, which has natural daylight and when I prepare the set, a story emerges. When I choose the subject, composition and light, I want to leave some things unresolved for the viewer, I don’t want to reveal everything. This doesn’t mean I know the answers, only that I leave the questions open for the viewers.

Sometimes I use objects I find at flea markets or random objects from daily life, other times, I have an image of an object I want to paint in my mind and I search for it through painting.

I’m excited by the beauty in the simplest things. When I see what I perceive as beautiful, I can paint it and share it with the viewer.

My method is simple, I usually draw a sketch and then paint. I don’t do any color studies before I start.

It’s important for me to find new challenges, whether different textures, formats, colors, new compositions, or anything for me to keep exploring.” – Dana Zaltzman